Work and home transitions: Exit and recovery time

Effects of exit and recovery time on families

Relationships

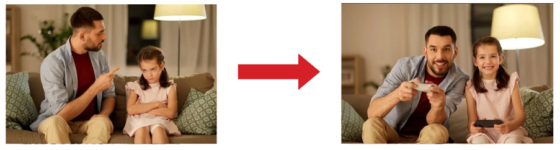

Without proper exit and recovery time, PSP may be physically present but not able to actively participate in family life. Families and couples can also experience conflict and tension. However, these types of routines can take time away from the family and add to an already long shift. Being aware of the value of this time is important. Families who create and manage exit and recovery time can enhance the quality of their time together.

Wellbeing

Family members may worry about how a PSP might feel or act when they get home (see anticipatory vigilance). This ongoing uncertainty causes stress and can threaten family wellbeing. No one is ever sure how PSP family members are going to be when they walk in the door after a shift. If the PSP family member is irritable or withdrawn, it affects everyone in the household. Conflict can arise and other family members can be upset and hurt.

Communication

When couples and families work together to manage exit and recovery time, everyone benefits. When PSP have downtime to unwind after a shift, they can return home ready to take on family roles. Families who talk about the why, when, and how of exit and recovery time reduce the risk of conflict and family tension. Being aware of the challenges of exit and recovery time and the impact on all family members is a first step in this process.

Preparing for re-entry

Research shows that, when exit and recovery time is not considered, PSP can spend their time at home thinking about the next shift. This may mean that they neglect family responsibilities and miss out on quality family time. Healthy exit and recovery time allows PSP to come home ready to engage in family activities. Active involvement benefits both PSP and their families.

Try: Skill-building Exercises

Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

References for this page (click to expand)

Bochantin, J. E. (2016). “Morning fog, spider webs, and escaping from Alcatraz”: Examining metaphors used by public safety employees and their families to help understand the relationship between work and family. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 214-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1073853

Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Taillieu, T., Turner, S., Krakauer, R., Anderson, G. S., MacPhee, R. S., Ricciardelli, R., Cramm, H. A., Groll, D., & McCreary, D. R. (2019). Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 51(1), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000115

McElheran, M., & Stelnicki, A. M. (2021). Functional disconnection and reconnection: an alternative strategy to stoicism in public safety personnel. European journal of psychotraumatology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1869399

Porter, K. L., & Henriksen, R. C. (2016). The phenomenological experience of first responder spouses. The Family Journal (Alexandria, Va.), 24(1), 44-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480715615651

Regehr, C., Dimitropoulos, G., Bright, E., George, S., & Henderson, J. (2005). Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of firefighters. Family Relations, 54(3), 423-435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00328.x

Ricciardelli, R., Carleton, R. N., Groll, D., & Cramm, H. (2018). Qualitatively unpacking Canadian public safety personnel experiences of trauma and their well-being. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 60(4), 566-577. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2017-0053.r2

Shakespeare-Finch, J., Smith, S., & Obst, P. (2002). Trauma, coping resources, and family functioning in emergency services personnel: A comparative study. Work & Stress, 16(3), 275-282. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0267837021000034584

Techera, U., Hallowell, M., Stambaugh, N., & Littlejohn, R. (2016) Causes and consequences of occupational fatigue: Meta-Analysis and systems model. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(10), 961-973. https://doi.org/10.1097/jom.0000000000000837

Van Gelderen, B. R., Bakker, A. B., Konijn, E. A., & Demerouti, E. (2011). Daily suppression of discrete emotions during the work of police service workers and criminal investigation officers. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24(5), 515-537. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10615806.2011.560665

Work and home transitions: Boundary confusion

Boundary confusion in PSP families happens when the boundaries between work and home are blurred. It can also mean that a person is unable to understand that certain behaviours are not appropriate (whether that is at work or at home). Inappropriate behaviours can affect that person’s relationships at work or at home or both.

Typically, there are different role expectations for people when they are at work and when they are at home. People behave differently depending on their role. These differences in behaviour are often necessary and require only minor adjustments. However, the adjustments for PSP can be significant. They may have difficulty transitioning from behaviours that work well at work to those needed in the home. Work behaviours that are more controlling, militaristic, and hypervigilant can spill over into the home.

PSP are at risk for boundary confusion because of the distinct differences between work and home roles. The blurring of roles and inappropriate behaviours at home can be uncomfortable for families and cause relationship tension and conflict. It is important to recognize the signs of boundary confusion and support work and home transitions that reduce the risk.

How might families experience PSP boundary confusion?

Overprotection and Hypervigilance

When PSP shift from a high risk work environment to home, it can be hard to switch off the behaviours that kept them safe at work. PSP might remain on high alert for any dangers (hypervigilance). They might also be overprotective of their SSOs or children because of what they witness at work. Introducing new rules at home and strict discipline for children, expecting absolute obedience, and reducing social contact can be signs of boundary confusion.

Withdrawal and Avoidance

As part of the transition home, PSP might decide not to share any information about work. They may do this to protect themselves and their families. At the same time, SSOs and children might choose not to share information with the PSP family member. They don’t want to cause the PSP family member any added worry (see anticipatory vigilance). All of this can cause a breakdown in communication, and adults and children can feel alone. Sometimes the decisions about what and how much to share can be difficult. Being aware of and talking together as a couple or family about the challenges can help reduce confusion.

Jealousy

PSP may bring their work home with them or their work might dominate couple conversations. SSOs may feel that PSP pay more attention to their work than their relationship or family. Co-worker camaraderie off the job can also result in jealousy. Team building and mutual support that is important on the job can develop friendships outside of work. SSOs may feel that PSP express themselves more freely with their co-workers which threatens their couple relationship. Boundary confusion results when there is too much focus on work and co-workers and too little focus on the couple relationship.

Heightened Expectations

PSP workplaces can have heightened expectations requiring strict order, rules, and consequences to get the job done. When there is boundary confusion, PSP might bring those same expectations home and expect to be listened to, followed, and obeyed. This can cause frustration for families. The kinds of expectations needed on the job may be inappropriate at home. PSP might also expect that, after a long or difficult shift, everything at home will be organized and in control. Unfortunately, this is often not a reality in family life. When these expectations are expressed, SSOs can feel disregarded and overworked.

Examples of boundary confusion

Click on the icon “i” for the example

Try: Skill-building Exercises

Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

References for this page (click to expand)

Agocs, T., Langan, D., & Sanders, C. B. (2015). Police mothers at home: Police work and danger-protection parenting practices. Gender & Society, 29(2), 265-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243214551157

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management.the Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472-491. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3363315

Bochantin, J. E. (2016). “Morning fog, spider webs, and escaping from Alcatraz”: Examining metaphors used by public safety employees and their families to help understand the relationship between work and family. Communication Monographs, 83(2), 214-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1073853

Fratesi, D. (2019) Police work and its effect on the family. Pine Bluff Police Department, Police Work and the Family. Retrieved July 15, 2022 from: https://www.cji.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/effects_on_family_paper.pdf

Helfers, R. C., Reynolds, P. D., & Scott, D. M. (2021). Being a blue blood: A phenomenological study on the lived experiences of police officers’ children. Police Quarterly, 24(2), 233-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611120964954

McElheran, M., & Stelnicki, A. M. (2021). Functional disconnection and reconnection: an alternative strategy to stoicism in public safety personnel. European journal of psychotraumatology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1869399

Miller, L. (2007). Police families: stresses, syndromes, and solutions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35(1), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180600698541

Ricciardelli, R., Carleton, R. N., Groll, D., & Cramm, H. (2018). Qualitatively unpacking Canadian public safety personnel experiences of trauma and their well-being. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 60(4), 566-577. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2017-0053.r2

Ungar, M. (2009). Overprotective parenting: Helping parents provide children the right amount of risk and responsibility. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 37(3), 258-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180802534247

Work and home transitions: Tension

PSP’s working schedules are not typical weekday, 9-5 schedules. This means that PSP couples and families have to work together to figure out household roles and responsibilities and make adjustments when the PSP is at work. Family members might have to take primary responsibility for household or parenting roles (e.g., extra-curriculars, medical appointments, homework help) while the PSP is on shift. Because of this, when PSP come home, there is a transition period where everyone has to “feel out” who is doing what. Also, because the PSP might feel pressure to keep work and family separate, PSP family members can feel frustrated by a lack of communication.

Because of the nature of PSP work, there are a lot of non-typical absences (see nonstandard schedules) and nonstandard re-entry times. This can result in changes in roles and routines depending on what shift a PSP is working. After working a series of long shifts, PSP may be off shift for a few days and take on more household and family responsibilities. However, open communication about who does what, when, and how is critical to avoid conflict.

Transitions for couples

Transitions for children

Children and youth can also experience transition tensions.

Try: Skill-building Exercises

Need Something More?

Check out our self-directed Spouse or Significant Other Wellbeing Course.

References for this page (click to expand)

Carrico, C. P. (2012). A look inside firefighter families: A qualitative study. PhD Thesis. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Daminger, A. (2019). The cognitive dimension of household labor. American Sociological Review, 84(4), 609-633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419859007

Friese, K. M. (2020). Cuffed together: A study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(4), 407-418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Harrison, D., & Albanese, P. (2012). The “Parentification” phenomenon as applied to adolescents living through parental military deployments. Canadian Journal of Family and Youth / Le Journal Canadien de Famille et de la Jeunesse, 4(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjfy16516

King, D. B. (2013). Daily dynamics of stress in Canadian paramedics and their spouses. PhD Thesis retrieved from: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/24/items/1.0074017

Regehr, C. (2005). Bringing the trauma home: Spouses of paramedics. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 10(2), 97-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020590908812

Thompson, A. J. (2012). Operational stress and the police marriage: A narrative study of police spouses. PhD Thesis retrieved from: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/24/items/1.0073056

Watkins, S. L., Shannon, M. A., Hurtado, D. A., Shea, S. A., & Bowles, N. P. (2021). Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(2), 137-148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23194